Carlos Correa Is Keeping the GIDP Alive

The Minnesota shortstop is one of the most prolific twin killers in baseball history. The rest of the league? Not so much.

Carlos Correa has grounded into six double plays this season. He doesn’t lead the league; that would be Junior Caminero, who has already racked up nine, putting him on pace for an even 50 by the end of the year. If Caminero keeps that up (he won’t), he would shatter the single-season record of 36, set by Jim Rice in 1984. Still, it’s Correa whose GIDP numbers I find most intriguing.

Correa has always been prone to double plays. Since the day of his debut, 10 years ago in June, only five major leaguers have grounded into more of them. However, in 2023, Correa took things to a new level. He set a single-season Twins record by grounding into 30 double plays. He did so in just 130 games and 580 trips to the plate. His 30 GIDPs were the most by any player in a season since Casey McGehee in 2014 (31) and the most on a per-PA basis (min. 500 PA) since A.J. Pierzynski in 2004 (27 GIDPs in 510 PA). Adjusted for era, Correa’s GIDPs-per-PA rate registered as the third highest of all time:

| Player | Year | GIDP | PA | GIDP Rate+ |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jimmy Bloodworth | 1943 | 29 | 519 | 281 |

| Jim Rice | 1985 | 35 | 608 | 276 |

| Carlos Correa | 2023 | 30 | 580 | 275 |

Correa’s historically pitiful GIDP performance in 2023 made what he did next all the more fascinating. In 2024, he produced an equally historical turnaround season. He hit just five groundball double plays, 25 fewer than the year before. Admittedly, he played significantly fewer games, but even on a rate basis, the difference was astounding. Never in his career had he grounded into two-outers at a lower clip. (Quick aside: Writers need synonyms, and if they don’t exist, it’s our job to make them up. Get ready.)

Using our nifty Season Stat Grid tool, I found the last player who decreased his GIDP total by 25 or more from one season to the next: Billy Hitchcock of the Philadelphia Athletics, who grounded into 30 double plays in 1950 and only two in 1951. It’s worth mentioning that I set the playing time minimum to one measly plate appearance each season. In other words, the sample included players who might have had hundreds of opportunities to ground into a double play one year and none the next. Yet, even from 2019 (a 162-game season) to 2020 (a 60-game season), the biggest drop-off in GIDPs belonged to Starlin Castro, who grounded into 23 paired putouts as a full-time player for the Marlins in 2019 and zero in 16 games for the Nationals the following year. All told, between 1951 and 2023, 143 players besides Correa had a season with at least 25 GIDPs, but none of them decreased that number by quite as much in the subsequent campaign. What’s more, Correa improved his wGDP (Weighted Grounded into Double Play Runs) by 6.1 runs from 2023 to ‘24. Hitchcock played about 50 years too early for wGDP, and as of this season, the stat has been retired, which means Correa’s +6.1 improvement goes down as the largest year-to-year bump in the metric’s short history.

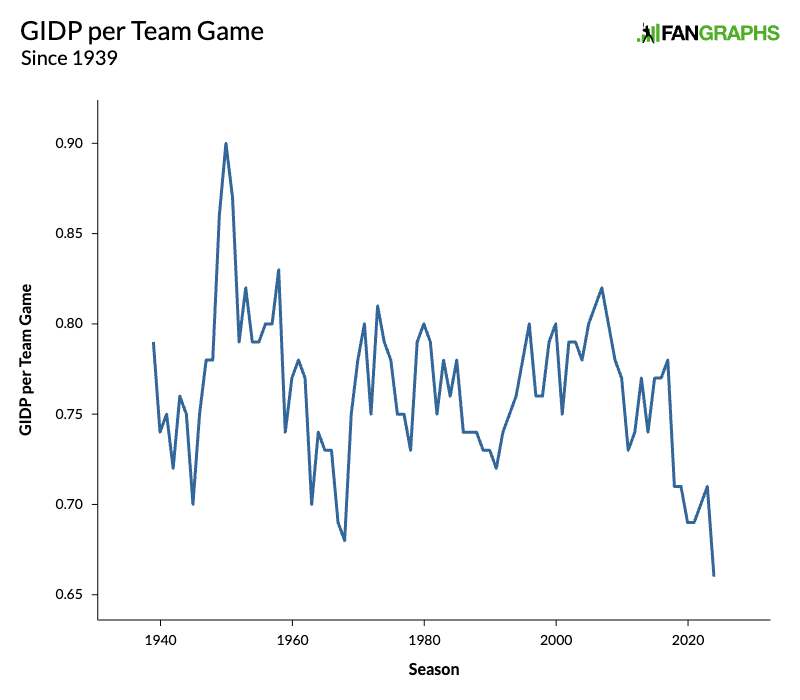

What really makes Correa’s GIDP antics over the past few years so interesting is the historical context in which they occurred. As you might have surmised, the reason his 2023 stands out as one of the worst GIDP seasons of all time is that twofold terminations were down around the league that year. Even more amusing, the already-low rate of GIDPs per game dropped off substantially in 2024. Indeed, it marked the fifth-lowest year-to-year decline on record. As a result, major league hitters grounded into double plays at the lowest rate in recorded history in the same season that Correa alone grounded into 25 fewer double plays than he had the year before. Coincidence? Well, yes. Correa’s improvement wasn’t nearly enough to explain the league-wide trend. But it makes for a nice fun fact.

Allow me to take a step back for a moment. Like most baseball fans, I love double plays when my favorite team is pitching, and nothing makes me grumpier when my team is up to bat. Rooting interest aside, however, I think double plays, even the most routine of them, are magnificent. As a Toronto resident, I went a long time without seeing a live baseball game in 2020 and ‘21. I still remember the first double play I saw in person after more than two years away from the ballpark. It was the most run-of-the-mill double play imaginable and still a remarkable display of athleticism. Ben Clemens described my feelings perfectly in a recent Five Things column:

“A well-turned double play, particularly if the degree of difficulty is high, is one of the most exciting plays in baseball. It features so many people operating in unison, there are usually close plays for at least one of the outs, and acrobatic pivots at second are just visually pleasing, period.”

Unfortunately, the faux pas de deux is dying. It’s a casualty of the modern game that I think is often overlooked. For all the conversations about disengagement rules, shift bans, bigger bases, rising strikeout rates, declining on-base percentages, and the infamous launch angle revolution, I have heard far less talk about the inevitable decline in GIDPs that is inextricably linked to all those other changes.

A groundball double play requires several conditions to be met. A batter must come to the plate with a runner on first and fewer than two outs. The batter must then hit the ball on the ground into the waiting glove of an infield defender. More strikeouts and fewer balls in play, more fly balls and fewer grounders, more stolen bases and fewer men on base, bigger bags and smaller defensive shifts – all of these reduce double plays. While those trends weren’t new in 2024, they all continued, and things came to a head.

The league-wide strikeout rate in 2024 was the fifth highest it had ever been. The league-wide OBP was at its second-lowest point in the past 50 years, while the percentage of plate appearances that ended in a single, a walk, or a hit-by-pitch was at its lowest in the past 75 years. In addition, stolen base attempts per game were at their highest since 1999. Altogether, this resulted in the lowest rate of GIDP opportunities per game (per Baseball Reference) since 2012 and, before that, since 1998. What’s more, the league’s groundball rate was the lowest it had been since at least 2002, and the percentage of plate appearances that ended with a ball in play was the fifth lowest in recorded history. Thus, the league-wide GIDPs-per-GIDP-opportunity rate was at its lowest since GIDPs were first tracked in both the NL and AL in 1939. So, opportunities were scarce and batters were unlikely to hit a groundball double play even when they had the chance to do so. The result? The league-wide rate of GIDPs per game reached an all-time low, nosediving below the previous nadir set in 1968:

I didn’t start working on this article with any sort of deeper message in mind. I wanted to write about double plays because I think they’re cool. Yet, I realized along the way that the declining groundball double play rate shines a light on so much of what’s going on in the modern game. This one little stat does a heck of a lot to encapsulate the state of major league baseball today. So far in 2025, the GIDP-per-game rate has continued to fall, decreasing from 0.66 to 0.63. That’s not quite as dramatic as the decline from 2023 to ‘24. However, if this holds, it would represent the largest drop-off over any two-year period since 1950-52. And this year, we can’t even pretend to pin it on Correa.

In 2023, Correa produced one of the worst GIDP seasons many of us have ever witnessed. Then, he made one of the biggest year-to-year improvements most of us have ever seen. I spent this past offseason wondering how he’d follow it up. It turns out, it would take him all of 23 games and 84 plate appearances to record more two-bird, one-stone groundouts in 2025 than he did the entire season before. Twins fans hoping he had finally turned a corner are surely disappointed. Instead, he’s giving a whole new meaning to the phrase twin killing; he ranks last on the team with -1.04 WPA, and his groundball double plays account for more than half of that.

Having grounded into six double plays before the end of April, Correa is on pace to outdo his 2023 campaign. That’s all the more (un)impressive considering how much the league average rate has dropped in just the past two years. Like I said about Caminero at the top, it’s wise not to put too much stock in early-season paces. Unlike Caminero, however, we’ve seen Correa maintain such a prolific pace of dual demises over a full season before. If he can do it again in 2025, he could very well end up with the worst era-adjusted GIDP season of all time. That might not be the kind of history anyone wants to make, but at least he’s doing his part to keep one of the most thrilling plays in baseball alive.